When I started this chapter of the SFF Bestiary, my knowledge of werewolf lore was minimal. A handful of films, a novel or two. I knew werewolves were a staple of urban fantasy, but I hadn’t read much of it. I didn’t realize how much I was going to learn, or how much fun it was going to be.

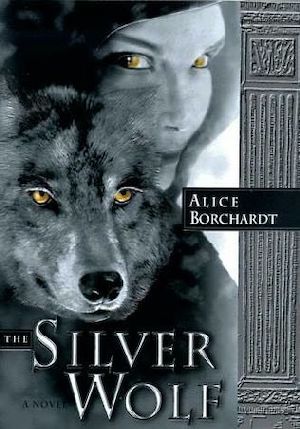

Thanks to a referral in comments (I have the best commenters), I now have a new author to add to my list of favorites. Alice Borchardt barely pinged my radar in the early years of the new millennium, when The Silver Wolf and its sequels were published. I may have heard her name in association with the far more famous Anne Rice, who happens to have been her sister, but I hadn’t read any of her works.

I’m working on remedying that now. The Silver Wolf is so far into my wheelhouse that it’s bumping up against the bulkhead. Historical fantasy. Early medieval. Rome in ruins but still defiantly alive. Charlemagne. With bonus “she knew horses.” And, of course, werewolves.

Borchardt did her homework. (Well, except for one persistent anachronism, but that’s where wheelhouse meets (over)critic, and it’s not crucial to the plot or the characters, so let it go, OK, brain?) She wrote well. Her world and characters are fully and deeply realized.

Hers is a grimdark Middle Ages. I can quibble that, too, rather strenuously—but at the time she was researching and writing, she was more or less mainstream. The Silver Wolf was first published in 1998, right after George R.R. Martin’s even darker medieval-oid A Game of Thrones appeared. It’s a similar world in both: men are horrid, women are oppressed, and life, like most of the populace, is nasty, brutal, and short.

I actually found myself casting some of the main characters as Martin characters. Notably, Lucilla as Ros, Elfgifa as Arya, and protagonist Regeane as Sansa. The parallels are not exact, but they’re close. The worldly-wise courtesan, the brash girlchild who refuses to play by conventional rules (and who adores her father), the naïve young princess who spends a great deal of time shrinking and whining and being abused. Regeane’s family is at least as awful as Martin might have imagined. They are, simply and conclusively, horrible.

What saved the opening scenes for me, and made the whole thing worthwhile, was the wolf of the title. As soon as she appeared, the story came alive. Regeane in the beginning is annoying to the point of tedium. She comes across as pure victim, with next to no ability to escape. But then comes the wolf.

If Regeane is pure victim, the wolf is pure wolf, sweet and wild. She has no sympathy for Regeane’s fears or foibles. She is entirely and unabashedly herself.

There’s plenty of plot going on here. Rome in the late seventh century AD is a cesspit of intrigue and political maneuvering, all of it rooted firmly in history. The Pope and the secular ruler of the city are violently at odds. A new king has risen in the distant realm of the Franks, a certain Charles, and he has imperial ambitions. He’ll be coming to take Italy. Italy means to be ready for him.

Regeane is caught square in the middle. Her mother was one of Charles’ many relations, and her mother’s brother and his Joffrey-esque son have played a part in parlaying that connection into a political coup: a marriage with a mercenary captain who happens to control the Alpine pass that Charles needs in order to invade Italy. Regeane’s feeble attempt to rebel flings her straight into the arms of the Pope’s faction, which in turn makes her a target for the Pope’s enemies.

While Regeane struggles to stay alive and unmaimed in Rome, Regeane’s future husband sets forth to claim his bride. Maeniel is, supposedly, a mercenary from Ireland. He leads a diverse band of warriors, many of whom are women. They are brash, outspoken, and happily uncivilized. There is also, we come to learn, rather more to them than meets the eye.

Good historical fantasy weaves history and fantasy so closely that the fantasy makes perfect sense within the history. The concept of the werewolf is a very old one, going back at least to ancient Greece. Rome itself was founded by a pair of feral children, twins raised by a she-wolf among the seven hills. Her logo, as we would say these days, was the wolf and twins.

Regeane with her inner and with increasing frequency outer wolf fits right into the mythos. The novel traces the path of her self-discovery. She makes friends and confronts enemies and gradually grows into her powers.

Most of werewolf lore, and all of it that I’ve been taking in of late, treats the transformation as a curse. The human version of the shifter may come to accept the wolf, but it’s a struggle. The wolf is savage, bloodthirsty, and difficult to control. Most of the shifter’s story focuses on either suppressing the wolf, or embracing the cool parts (super strength, super senses, superfast healing) but fighting to keep the human mind and morals on top.

If the wolf takes over, the human half may not survive. The only solution, if that happens, is to kill the wolf. To put it down, as one does any other vicious animal. The werewolf’s story is a tragedy that most often ends in death.

Borchardt’s werewolves are a refreshing antidote. In her world, humans are the curse. There are good ones, innocents and people of goodwill, mostly, insofar as they can. But most are brutal, amoral, murderous, cruel, greedy—the list goes on.

Wolves by contrast are straightforward. They hunt, they kill. They eat what they kill—and that includes humans. They’re predators. That’s who they are.

They’re also strongly social creatures. They run, by nature, in packs. They don’t suffer from human complexes about sex. They’re deeply attuned to the natural world.

Buy the Book

The Crane Husband

For Regeane, humanity is a constant battle for survival, not simply as a person but as a person who happens to be other than human. The wolf knows exactly who she is and what she’s for. The only way Regeane can be whole is to embrace both halves of herself, and let them become one.

It’s not a smooth process. As a human, she’s a pawn in multiple political and familial games. The wolf is in constant danger of being exposed and killed. Her friends all have agendas, many of which revolve around using her or the people she loves or is connected with. Her enemies are determined to obliterate her as painfully and as thoroughly as possible.

I’m not going to spoil the story. I am just going to say that I found the ending quite satisfying. It’s not totally inevitable, either; it holds the suspense right up until the last scene.

I love that the wolf is the good guy here. That the world is so fully realized and the characters so vivid. They may come across initially as tropes, but as the story unfolds, they develop more and more as individuals. Regeane and Sansa share a great deal, from beginning to end (and as a bonus, the wolf and Regeane get to be one being), but Regeane, ultimately, is her own person. Whole and complete in all that she is.

One image stays with me. It’s perfect in its moment. It’s the wolf rolling in a field of flowers, all four paws in the air, her whole body an expression of joy. That’s pretty much how I felt as I read her story.

Judith Tarr is a lifelong horse person. She supports her habit by writing works of fantasy and science fiction as well as historical novels, many of which have been published as ebooks. She’s written a primer for writers who want to write about horses: Writing Horses: The Fine Art of Getting It Right. She lives near Tucson, Arizona with a herd of Lipizzans, a clowder of cats, and a blue-eyed dog.